Investigate Nuraddin Jumaniyazov’s Suspicious Death

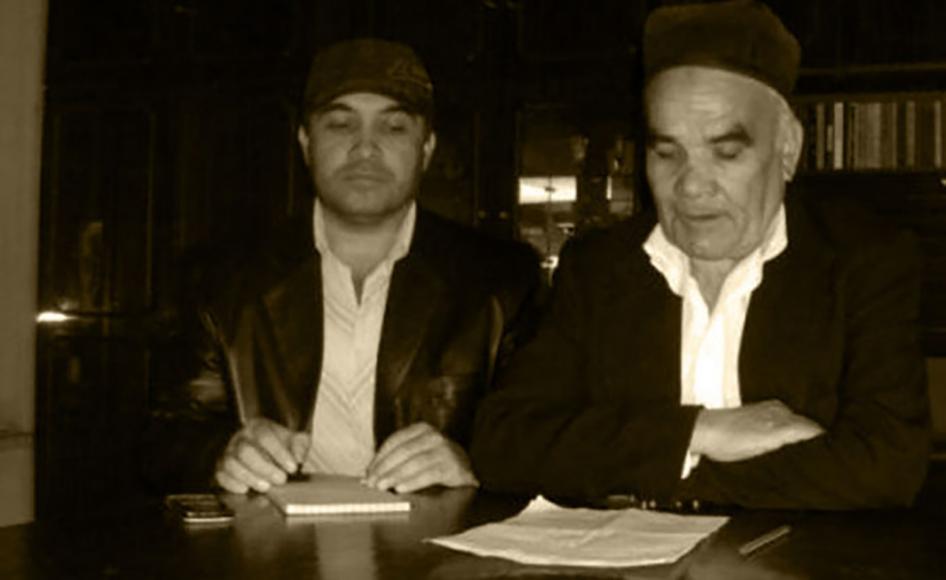

Imprisoned Uzbek labor activists Nuraddin Jumaniyozov (right), who died in prison on December 31, 2016, and Fahriddin Tillayev.

© 2014 Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights

(Bishkek) – The Uzbek government should immediately allow an independent investigation into the enforced disappearance and death in prison of a human rights and opposition activist, Human Rights Watch said today. On June 16, 2017, Nuraddin Jumaniyazov’s wife, Gulnora Rahmonova, reported that her husband had died in prison on December 31, 2016, from tuberculosis and diabetes-related complications.

Jumaniyazov was unlawfully imprisoned in 2014 on politically motivated charges. Uzbek authorities had refused to reveal his whereabouts or allow him any contact with his family or attorney since 2015, despite numerous calls by Human Rights Watch and other organizations to seek information about his situation. The refusal to provide information on the fate or whereabouts of a person deprived of their liberty constitutes an enforced disappearance, a crime under international law, and is prohibited in all circumstances.

“Nuraddin Jumaniyazov, who should have never been imprisoned, died in prison, hidden from his loved ones and the world,” said Steve Swerdlow, Central Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The tragic death of this human rights defender in Uzbekistan casts serious doubt on the government’s claims that the country is undergoing meaningful reforms.”

Jumaniyazov, a rights activist and member of the opposition Erk (Freedom) party, was sentenced in March 2014 to eight years and three months in prison on human trafficking charges along with his fellow activist, Fakhriddin Tillaev, following a trial that did not meet international human rights standards. Jumaniyazov had also been a member of the Mazlum (The Oppressed) Human Rights Center since 2003. Jumaniyazov and Tillaev began advocating workers’ rights in 2005. In 2012, the two founded the Union of Independent Trade Unions, which protects the rights of migrant workers. Jumaniyazov headed its Tashkent chapter.

On December 28, 2013, Tashkent police interrogated Jumaniyazov after two Uzbek citizens, Farhod Pardaev and Erkin Erdanov, alleged that he and Tillaev arranged their employment in Kazakhstan, where they said they had been mistreated.

Jumaniyazov’s lawyer, Polina Braunerg, a well-known human rights attorney who had been denied permission to leave Uzbekistan to obtain medical treatment abroad for at least three years, died after suffering a stroke in May 2017. She earlier told Human Rights Watch that the investigation against Jumaniyazov and Tillaev was marred by serious procedural violations.

Police arrested them on January 2, 2014, and took them to a Tashkent prison, but falsified materials to indicate January 4 as the date of arrest. Investigators did not provide Tillaev’s or Jumaniyazov’s lawyers sufficient time to review the evidence in the case, conducting all interrogations, including of the defendants, in a single day before advancing the case to trial. The court completed the trial in just two hours, basing the conviction solely on the testimony of two witnesses who admitted that they had never seen the defendants nor had any relationship with them.

Braunerg said that police tortured both Jumaniyazov and Tillaev in pretrial custody. The police allegedly stuck needles between Tillaev’s fingers and toes, and forced him to stand for hours under a dripping faucet, causing a severe headache. No judicial or prison authorities meaningfully investigated the torture allegations.

Jumaniyazov was last seen in public at his appellate hearing in April 2014, during which he asked his lawyer to help him obtain medicine to treat his tuberculosis and diabetes. Both Jumaniyazov and Tillaev were sent to a prison in Navoi, southwestern Uzbekistan, to serve out their sentences, where Tillaev is currently being held.

Beginning in October 2014, Braunerg sought permission to visit with Jumaniyazov, but was repeatedly denied access by prison officials.

During a July 2015 review of Uzbekistan’s compliance with its commitments under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the United Nations Human Rights Committee questioned members of the Uzbek government delegation about Jumaniyazov’s whereabouts and health condition, asking Tashkent to provide the information within two weeks. Uzbek authorities ignored the committee’s requests.

Prison officials again blocked Braunerg’s attempts to locate and meet with Jumaniyazov following the UN review, stating misleadingly that a meeting could only be granted if Jumaniyazov made a written request, in violation of article 10 of Uzbekistan’s Criminal Procedure Code.

In February 2017, two months after Jumaniyazov’s death in a Tashkent prison hospital, prison officials apparently agreed to Braunerg’s request to visit with her client in a prison hospital in the city of Qarshi, where she had been told Jumaniyazov was then being held. But when Braunerg arrived, officials told her he had been moved back to a prison in Navoi. However, officials at the Navoi prison denied holding a prisoner by that name.

The United Nations Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment provides that medical care and treatment shall be provided to detainees whenever necessary and free of charge. The Body of Principles also provide that a detainee “shall be entitled to communicate and consult with his legal counsel.” Whenever a person dies in detention, “an inquiry into the cause of death … shall be held by a judicial or other authority.” In addition, “[t]he findings of such inquiry … shall be made available upon request.”

“The cruel cat and mouse game Uzbek authorities played with Jumaniyazov’s lawyer and UN rights experts to hide his whereabouts and condition illustrates a shocking and callous disregard for the health and basic rights of detainees,” Swerdlow said. “The Uzbek government should get serious about implementing reforms, beginning with releasing wrongfully held activists and meaningfully investigating Jumaniyazov’s death.”

https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/23/uzbekistan-imprisoned-dissident-dies-custody